Postmortem of a Rhodes Loser

Airing out some business.

Becoming one of Harvard’s Rhodes Scholars is a lot like taking a vacation to North Korea — when all is said and done, you’re gonna get interviewed by the CIA. Or in Harvard’s case, you get sent a detailed questionnaire from the Fellowships office, asking everything from the questions of your interview to the composition of your panel and the clothes you wore. One can read those success stories by visiting Cambridge’s local SCIF (the URAF townhouse near Kirkland) and asking to see “the binders.”

The winners-only strategy is not so much a commitment to survivorship bias, as it is because Harvard enjoys such an overwhelming number of Rhodes winners that binders of its losing narratives would fill an entire room. But I think there is still something to be learned from our losers. For example:

Because I am a masochist, I spent a November weekend hanging out in the lobby of a nondescript, recently renovated office in the Watergate complex with thirteen other highly driven, accomplished students from top universities around the country. We were there to interview for two slots for the Rhodes Scholarship, reserved for U.S. District Five — D.C., Maryland, and Delaware. Suffice to say, the publisher of a local gossip blog that brags about tax evasion did not receive one of the world’s most prestigious academic honors. But because I am a masochist, I will tell you how it went down.

That’s the dirty little secret of Harvard’s fellowship-seeking, as best I can tell: one is so perfectly positioned for success that the opportunity is hers to lose.

Let’s start from the beginning. Anyone who knows me could tell you that I dream(ed) of speed-running the life and career of soon-to-be-former Secretary of Transportation Pete Buttigieg. I had figured I was in good shape, when I transferred to Harvard with the registrar’s guarantee that I could finish my degree in two years’ time. (I failed to become a bonafide IOP Kid, but let’s face it, Real Haters probably exerts about the same level of influence over the IOP as its student leadership anyway.) I knew that if I wanted to stand any chance of losing several statewide elections, marrying a guy seven years my junior, and having middle-aged women excitedly tweet about my Fox News appearances — the logical next step was to apply for Harvard’s endorsement towards the Rhodes. Wouldn’t that demonstrate fantastic commitment to the bit? I applied in August; I was one of thirty-ish seniors to get the endorsement(!); we were off to the races.

The first order of business was to sit down with one of my house’s “fellowships tutors,” former Rhodes/Marshall/etc. winners whom Harvard keeps on retainer to help the university win only more, and greater, elite fellowships. Harvard annually wins more than double the Rhodeses of any other school in the world; this is accomplished — entirely within the scholarship’s strict rules for student independence — by careful guidance, hand-holding, and general coddling. My tutor (a brilliant, incredibly kind grad student studying South American history) made himself available at all hours for me to bounce ideas off, advising me on everything from ‘resume line-items to highlight,’ to ‘how to get a professional-looking headshot ASAP.’ By God, I was gonna acquire the requisite eight rec letters, institutional endorsement letter, personal statement, and academic statement. With Harvard’s help, I was going to do it perfectly.

That’s the dirty little secret of Harvard’s fellowship-seeking, as best I can tell: one is so perfectly positioned for success that the opportunity is hers to lose. We are told at the outset that only one-quarter of endorsed students are selected to interview in the final round. This statistic is true — of normal schools. Conversely, I actually did not hear of a Harvard-endorsed student not making it to the district interviews. Sure enough, by the end of October, I had been invited back home to D.C. for the final round: an evening cocktail party, to be followed by individual twenty-minute interviews.

So Harvard is invariably left with a problem: how to turn thirty of its highest-achieving twenty-two-year-old psychopaths into charming little conversationalists? There must have been some concern about our capacity to dazzle in the party section of the weekend, because I was promptly invited to a “mocktail party” for finalists. We assembled in our best business attire (save for one Crimson executive who wore jeans) in the Leverett library to be instructed. We were lured there with promises of the classic student delicacies (berries and cheese) and sent around the room to practice making eye contact while shaking hands.

There was also the small matter of “the article” — a Fifteen Minutes piece, published hours before Harvard’s Rhodes finalists descended upon Boston Logan, which landed in senior-class groupchats with the explosive force of the Trinity test. The article detailed, at length, the process and privileges of Harvard’s Rhodes scholarship acquisition; I had advance warning of its existence because I had repeatedly declined to comment on-the-record. (Famously, I never talk to the press. Please do not fact-check me on this.)

But my takes wouldn’t have been helpful, in any case — the meat of the article was devoted to a Crimson executive’s grievance-airing about the comparatively insufficient resources devoted to Currier House for his preparation as a Rhodes finalist. The article concluded that Currier House was, relatively speaking, turbo-fucked in the weekend ahead. I’m not strictly sure why one would not only make broad extrapolations about rare events — but also, why one would publish the findings just days before another round of occurrences that could totally turn your findings on its head. I guess this is why I’m not a student journalist.

I had other problems to worry about, anyway. With the help of my friends and Harvard’s massive institutional resources, I threw myself at preparing for my interview. It was a miserable two weeks. I picked out dresses, at length and in granular detail, with the advice and consent of no fewer than five adult professional women. I started and ended every day by reading through my resume. When my nerves devolved to the point of hysteria — unhelped by my asthmatic self being exposed to pneumonia at the last minute — and I began vomiting every morning, I subsisted on a diet of thickened Pedialyte, saltines, and dhall orange juice. (Word of advice: do not do this.)

“Stop doing that thing with your voice,” was the primary piece of feedback that the tutors gave when Mather held mock-interview sessions.

“What ‘thing’?”

“That thing you do, where you speak really softly and make intense eye contact with your hands folded in front of you. Like Meryl Streep in The Devil Wears Prada.”

Every day after that, I practiced smiling and laughing in front of the mirror, hoping that it would stick.

I will say this about the Rhodes interviews: One becomes accustomed to being a big fish in a small pond. I certainly did, at Scripps. I went to Harvard, and was pleasantly surprised to discover that my scale transferred too — I could still be a ‘big fish’ among the heavyweights. Then, finally, at the Watergate complex I met my match.

Returning home to Washington, I felt ‘good.’ I felt confident. I had received every privilege in my preparation; I knew that I had behind me the full backing of the world’s most powerful educational institution — evidenced, in the immediate sense, by being given the cell phone number of the fellowships office to dial in the event of an emergency needing the intervention of the university’s lawyers.

Let’s make one more thing clear, by the way — I looked amazing. Every single makeup tutorial I had ever watched in my entire life came to bear on my bathroom sink circa Friday, November 15th. To the cocktail party, I wore a beautiful tan dress that felt like being wrapped in pajamas. The next day, I — read, my mother — had selected a blue wool dress, to be worn with matching low suede heels over semi-sheer hose, which kept ripping. (“What’s hose?” guys my age have invariably asked when I complained about the subject.)

The next day, I presented myself bright and early (across-the-board call time was 8:30; my interview was scheduled for 2:45) at the Watergate complex. With nothing to do, and no one willing to play board games with me, I posted up next to the electrical outlets with a friendly, funny Georgetown student named Noa, who studied American prisons and spoke eagerly about a wrongfully convicted man whom she had helped to free this year. (Hand to the Episcopal Lord God Almighty, if you had asked me by 4pm not only, “to whom would the female slot likely go,” but, “to whom should the award go” — I would have said Noa in a heartbeat.)

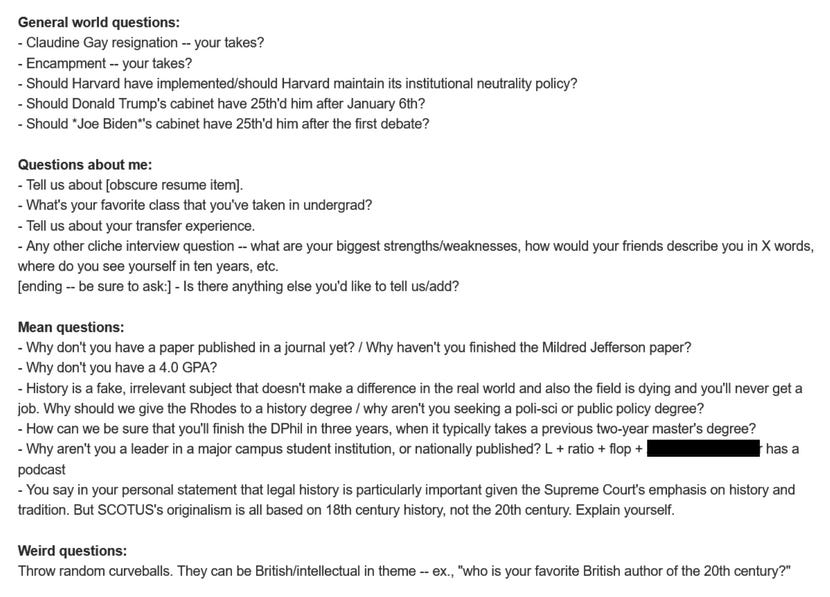

The received wisdom of these interviews is that they are aggressive, mean, and altogether painful. I caught wind of a guy out West who was asked to translate a sentence from Swedish on the spot (he took the language first-semester freshman year), identify the speaker of a quote from the Bible (he had written in his statement about his intent to attend church at Oxford), and answer a statistics question about coins in a ziploc bag (????). One Harvard professor warned me that I should brace myself for the interview committee to demean my field of study. (I suspected, though of course did not express, that this was perhaps because her students concentrated in Women, Gender, and Sexuality Studies.)

I felt, in the general sense, that I interviewed fine. I was brought to sit around a massive, heavy white marble table in the chair’s office; I don’t know that I’ll ever forget the thin seam running across the surface, nor that I could not for the life of me figure out a non-awkward way to make eye contact with the judges to my immediate sides. The committee was so nice — even while picking apart my responses — that I had no opportunity to clam up as I had in my mock-interview at Mather, when my tutor asked me to name two books on the Yom Kippur War whose historiographical intervention I disagreed with. The judges asked what I thought the Onion ought to do with its purchase of InfoWars, and how I felt the 1980 election stacked up against 2024. Then I was dismissed again for the committee to deliberate.

In the past decade-ish, the district had broadly followed the same pattern in selecting winners: one male and one female; one from an Ivy or other elite university, and the other from a local school. (Georgetown might count towards either metric.) There was no way to assort into potential winning coalitions, though. The women from the local schools each could have been paired with the men from the elite schools, and vice versa; the local men could have been matched with any number of out-of-state female students. Were I to win, I would inevitably win with the Naval Academy guy (who cheerfully walked me through the finer points of explosive ordnance disposal) or the Georgetown student journalist (who worked through several books while waiting for his interview).

But let’s face it. I got my hopes up. Individually, we all did. It’s like the scene in Conclave where Stanley Tucci asks Ralph Fiennes what he would choose as his regnal name, were he to be elected pope. And Ralph Fiennes, who had already told Stanley Tucci that he absolutely never wanted to become pope, immediately says yeah I would choose John because I’m gonna die soon, or something. And then they leave the Getty Museum to go back into the Sistine Chapel and conclave even harder.

You may have also observed that I share first and last letters of my name with Noa. This became momentarily problematic when the committee returned, and — after giving a brief speech about how we were all winners, etc. — the chair announced, in his gravelly voice, that the winners were N—a and David.

I am usually very bad at taking hints. (My suitemates hate when I third-wheel them and their boyfriends in our common room.) But given that everyone was looking at her, and no one was looking at me, over the course of a very long second I realized what the title already informed you of — the modal outcome had occurred.

The end. We shook hands with the committee and hustled out the door in a hurry; it was getting late. Downstairs, I observed with amusement that some judges preferred to wait for their Ubers outside in the rain, rather than stand in the lobby with the finalists whom they had just unceremoniously rejected. None of us felt like talking much, anyway. The committee had previously spoken highly of the “lifelong friendships” we might form, and that we ought to go out for drinks afterwards. But everyone was just flat wiped by the brutality of the long day. We went home.

Last year, Harvard made out with a whopping nine of the thirty-two U.S. scholarships. This year, it was only (“only”) five. After-the-fact, a few other finalists expressed to me that the course-correction, and being caught up in its wave, had done devastating damage to their self-esteem. They felt they would win; they failed; it stung.

Not to erroneously imply that I have my life together in any meaningful way, but — can’t relate?? There is an element of “Special Boy, Poorly Served” Syndrome inherent to emerging into Rhodes loserdom with anything less than intense gratitude and pleasure to have made it so far. The disappointment that I felt (still feel?) was the mild frustration felt across the workforce every day: to have poured my heart, soul, and labor-hours into an application, only to be unceremoniously rejected.

I am, suffice to say, not all that broken up about having lost the Rhodes. There is now a mass-printed certificate on my dorm wall, in case this article ever stands as insufficient proof that the line, “Finalist, District Five, Rhodes Scholarship, 2024” is true. And if I am ever held at gunpoint, told to list two books on the Yom Kippur War whose historiographical intervention I disagree with — I will be seized by the taste of lemon-lime Pedialyte as I cry, “Martin Indyk’s Master of the Game and Salim Yaqub’s ‘Short-term Success at the Expense of Enduring Peace’!”